The Badlands Be Bangin' Part I

Badlands National Park, South Dakota

by Cassia Reynolds

by Cassia Reynolds

by Cassia Reynolds

Keep it chronological! Check out my other two installations on Devils Tower or risk a serious case of FOMO: Devils Tower: A Massive Mystery Rock & Devils Tower: The Perimeter

Three..Two...Go!

I heaved my torso up and over the boulder, my fingertips digging into rough stone, the rubber soles of my hiking boots bouncing off the slanted edge of a neighboring rock. When I’d dragged myself to the top, I turned to take in the view behind me: dark pine needles, crusty bark chunks, and far below, hikers milling about. The hot sun blazed down on the world, casting deep shadows in the crevices and browning my shoulders.

I dove forward, using all the momentum I could muster to throw myself across the gap to the next landing.

I’d been scaling boulders for at least forty-five minutes and I was only three-quarters of the way up Devils Tower’s rock fields, a graveyard of shed stone. As I moved further from the main trail, the wild hills of Wyoming became visible over the treetops of the pines. Near the highest point, I took a break, sinking down, my legs dangling off the edge of a boulder. I inspected the chartreuse lichen that grew on these Tower bits-and-pieces and wondered if this was what gave it the gray-green hue.

While resting, an unnatural glint of light caught my eye. When I turned toward it I could only see a single persistent pine wedged between the boulders off to my right. Before I moved away, the breeze came back and the reflection returned. There was something over there.

Treasure?

I clambered over to the skinny, twisted trees, ducked between the lowest branches, and pulled myself into their shade. And suddenly I was surrounded by colorful knots of fabric. Strips of faded red, yellow, and cream fluttered and fell with the breeze. And in the middle of it all, I found the light-reflecting culprit, a teeny dreamcatcher decorated with glittering green beads.

Tied to the dreamcatcher was a card with a print of a rose. It had been slipped into a plastic sheath to protect it from the elements. Drops of condensation stuck to transparent walls. And dangling down from the same bunch was a slender, metal branding tool with one end molded into a skinny “P.”

I admired the bundle as it spun around and around with the wind.

What I’d stumbled across was someone’s personal prayer offering to Devils Tower, a part of one of many traditional ceremonial activities still practiced by Native Americans in the Midwest, today. Over twenty tribes are connected to Devils Tower and many have their own creation story for this strange rock formation.

The foundation of many of these legends is similar: a group of children or a woman meet a gigantic bear in the woods. The bear chases them and they pray to the heavens, begging for help. The ground beneath their feet rises up, carrying them into the sky. The angry bear tries to climb the newly-and-spiritually-formed rock, dragging his claws down the sides and leaving the column-like ridges that still exist today.

In my favorite version of this tale, told by the Kiowa, it is a group of young sisters that runs from the bear. When they are lifted to the sky, they are taken so high that they become a part of night and survive today as the twinkling Big Dipper constellation.

Lying on my back below the pine, I squinted up at Devils Tower. From upside down, the ridges all along the sides really did look like claw marks.

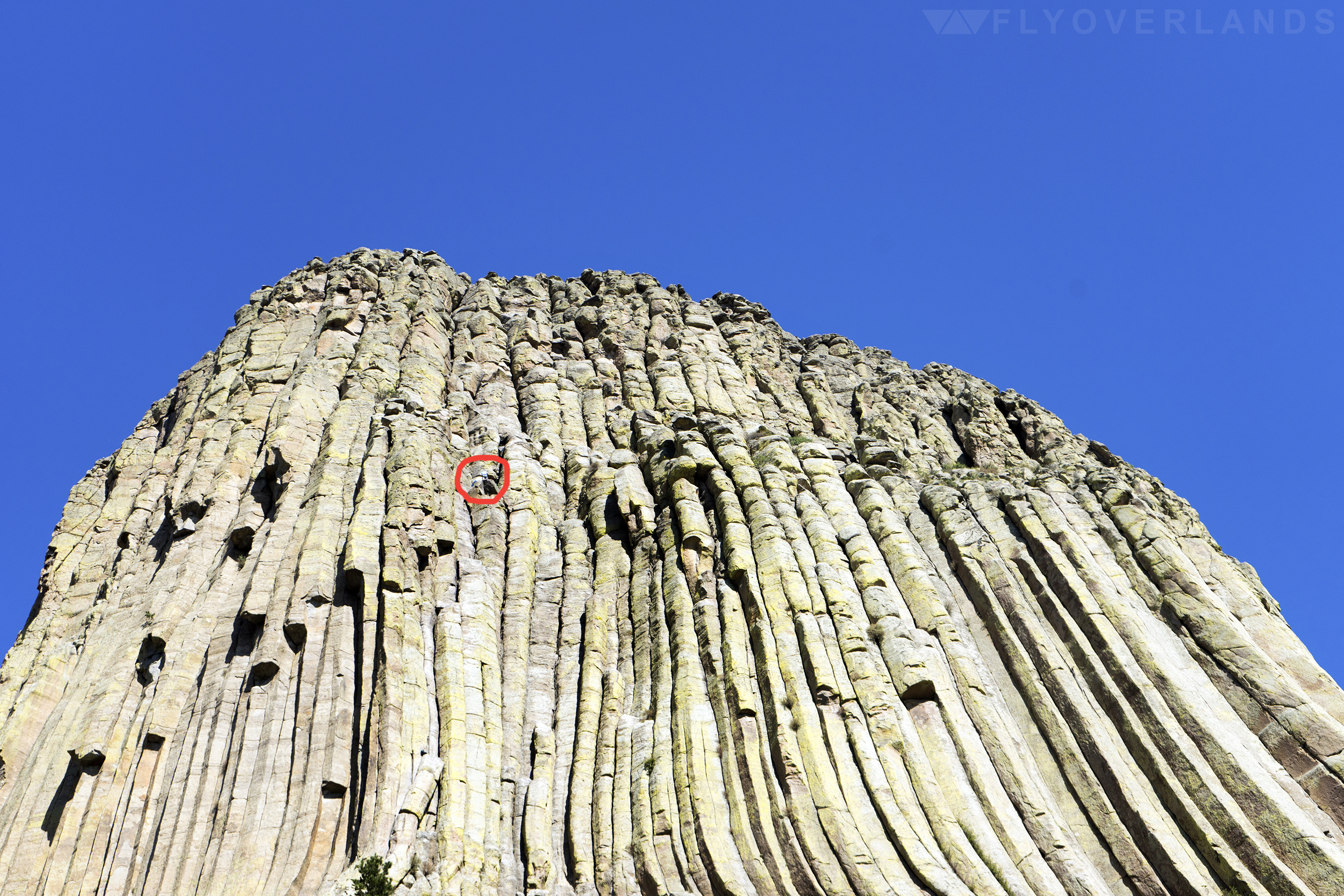

As cool as my excursion across the boulder fields was, the real adventure-seekers visit this site to crack climb its steep, choppy walls. I’m talking 127-hours style, jam-your-fingers-in-gaps-between-the-rocks-to-propel-your-body-upwards climbing. The kind of special technique that has its own equipment and grading scale. Devils Tower has multiple crack climbing routes with varying degrees of difficulty, many of which are advanced.

I saw multiple hikers on their way to the top while I wandered around the boulder fields and along the mostly-flat trails. Their tiny figures were just blobs of bright color dancing between the ledges.

While the art of crack climbing is badass, the increase of climbers at Devils Tower has caused a stir over the years. Many Native American tribes consider this recreational climbing a desecration of the sacred site. To compromise, the National Park Service has set aside the month of June, in which many Native American celebrations surrounding The Tower occur, as “Voluntary Climbing Closure” month. It’s not mandatory to respect this tradition, but it’s suggested, and the the act has resulted in an 80% reduction of climbs during the month of June.

It’s a start.

The confusion and miscommunication between Native Americans and the American Government has been a long running theme (as we all know but especially) at this first national monument. Long before it was dubbed Devils Tower, it was known to Native Americans, among other names, as Bear Lodge or Bear Rock. The oh-so-Satanic namesake realised from a misinterpretation of the original name in 1875. A colonel interpreted “Bear Tower” as “Bad God’s Tower” which eventually led to “Devils Tower.” Still no explanation for that (aggravating) missing apostrophe, though.

The idea of a national monument, where the US government rushes to decree ownership over a piece of land or a memorial, offers a glimpse into the minds of American leaders of the past; what makes each one important and why? And most importantly, to whom are they important?

I sat up and brushed off the dust from my back, preparing to leave the little dreamcatcher and the prayer cloths, and as I did, I wondered if Devils Tower was less a tourist attraction and more a sacred space. And if this mini-sanctuary was hidden on purpose by its founders.

As I contemplated the teachings about Native American beliefs from my middle-school-days, I realized that ownership of this land didn’t matter. There was no “ownership” of nature, no real way to say that a rock was America’s besides a piece of paper with a list of “rights” on it. It was all Mother Nature’s, and that’s something that we need to respect.

A piece of paper can fade, can flutter away in the wind.

by Samantha Adler

Florida palm trees, luxurious naps and bingo: these are the things retirement dreams are made of.

But, if you travel up to woodsy New Hampshire and ask Maureen and Larry Gelo they’d beg to differ. A couple of retirement rebels, these two fill their time seeking new adventures on America’s open roads, breaking away from the status quo of retirees.

The two lived, worked and raised their children in Connecticut. He worked as a police officer in a small town on the shore and she worked as a nanny. Larry’s a handyman who can fix all and create any device you’d ever need from scratch. Maureen’s gentle and loving with a dash of cheeky spunk. After retiring at age of 62, they bought a motorhome and set off on a series of spontaneous road trips in North America, driven by curiosity and an unfulfilled wanderlust. It’s been over a decade and they’re still going, insisting there is so much to see in this big, beautiful country of ours.

This pair of serial roadtrippers happen to be my grandparents (+10 cool points for me) and two of the biggest supporters of the road trip. I recently visited them in Unity, New Hampshire, their home base. When they’re not out on the road, Larry does woodwork with materials from the forest behind their house (Check out some of his amazing work), visit friends, hike and enjoy their rugged New England home.

Before settling down over the kitchen table, we went on a short hike in the nearby Quechee Gorge. A few remaining leaves hung off wiry branches, clinging on against the chilly late autumn breeze. We got home, tore off hiking boots and unbundled. After putting a log on the furnace, we gathered around a plate of brownies and they shared their stories, travel advice and all their coveted road trip knowledge in their usual hilarious banter.

First off, why the travel retirement?

L: There’s a lot of places we’ve never been and we’d like to go there.

M: That pretty much says it all. We just wanted to travel and see this beautiful country.

Why roadtripping in particular?

L: Because you can see a lot more. And with a camper you can stop wherever, whenever and for as long as you want.

M: To get off the beaten path and see things. We’ve had so many surprises, especially in these little towns along the way. [There was] one place in Nebraska we ended up. It was the end of the day and we were tired. We just about got into this parking lot, when we saw there was a museum. Well, we ended up staying there for three more days because this museum was blocks long. A man had collected everything from soup to nuts; from cars to buttons. And he had all these buildings with all these wonderful things, like the earliest telephone. We found out that he was the creator of bubble wrap! And he just collected for years and years and years. But like I said when we pulled into this place it looked like nothing, it was just a place we stopped at because it was the end of the day and we were tired. So that’s the wonderful thing about traveling across this country in a vehicle.

Did you travel when you were younger?

M: I think the farthest we ever went was to visit my father’s sister in New York. And that was about three or four times in my childhood. Neither of my parents liked to travel, they were homebodies. So that gave me the wanderlust.

L: When I was single in the service and my teenage years, I used to travel down the East Coast, and that was it. But I did get to go to college in Alaska and loved it. About forty years ago we got the chance to take a cruise up there and loved it. Then we went back and spent eight or ten weeks traveling around in the motorhome.

What was your first road trip?

M: We had a trailer and we went up to Canada, Quebec and Niagara falls, on both sides. There again, we found this wonderful little town that we would have never found if we weren’t riding around.

L: We first started with a truck, we camped in the back of the truck, then we got a little trailer, then we got a little bigger trailer and then we decided [to get the RV] when we got close to retirement.

What was the best trip or route you’ve taken?

L: I think Alaska was probably the greatest. They’ve all been great. One time we went down Route 50 from the East Coast all the way out to California. It was the old 1950/60’s. Most of it’s disappeared by now, but it was kind of nostalgic and off the beaten path. It was stuff we remembered from when we were young.

M: Route 66.

L: Yea, a lot of it was Route 66. Another time we went along the Canadian border all the way west, then down the coast to San Francisco and then back along the southern coast. That was an amazing trip.

What was the craziest thing you saw because you were driving?

L: We’ve seen just about everything. We’ve been in tornados, major thunderstorms, hailstorms, windstorms where we thought the camper was going to flip over. Anything you can think of we’ve been near it, too near it for comfort or right in the middle of it.

Have you made any friends along the way?

L: We’ve met all sorts of people. You never know who you’re going to run into. We stopped in one place in Canada and met people we’ve been in touch with for seven or eight years now.

M: All nice people from all walks of life.

L: Everyplace you stop you should talk to somebody. You’ll talk about where you’ve been and where you’re going and they’ll tell you what you should go and see. And if they’ve been to places you’ve already been, they’ll tell you about places you missed after you thought you’ve seen everything there is to see. We went to Wall Drugs a few times going across country. It’s a big, big drug store and big tourist attraction. And almost across the street, were the Badlands. We drove right by it. The third time we finally figured it out after chatting with people.

What are the best things you’ve picked up along the way?

L: She likes to shop. We had to go all the way to Alaska to go to Walmart.

M: No. My best souvenirs were in Sequoia National Park, we filled our trunk with great big pinecones.

L: Then we found out it was illegal.

M: And then I got a piece of wood from the Petrified Forest. Which was...another illegal thing. Nothing I bought. I have a chunk of rock from the base of Crazy Horse. And that was legal! They said I could take it.

L: Every place we’ve gone to I’ve gotten a walking stick emblem.

I know you’ve had some run-ins with pretty large critters.

L: We saw every animal you could think of in Alaska: mountain lions, moose, bears. I’ve walked up on a moose. Not intentionally. I was walking along the road and right next to me a moose started snorting. I said “oh that’s not a smart idea.” I kept walking and he went back on to minding his own business.

Advice for aspiring roadtrippers?

L: It’s the most exciting way in the world to go. You don’t have to go on an airplane and go through all that crap. Travel as much as you can. You get a whole, totally different outlook on the world. You see it’s more than this little town you live in.

M: Enjoy the ride and the surprises. In Saint Louis we ended up seeing the Clydesdales from the Budweiser commercials at Grant’s Farm. That was a surprise that we came upon. It was in this beautiful nature park that had all types of animals. And it was totally free.

L: Talk to everyone you can talk to.

M: I like stopping at visitors centers because you can get all the information you need. It’s always good to stop there.

L: If you see something interesting you should stop. The most important thing about traveling like this is being able to stop when you see something interesting and if you don’t make your destination, fine.

The one place you must see in the US?

M: Grand Tetons.

L: When we were traveling to a balloon festival in Arizona, we hit every presidential library in the country. That was amazing, I never knew the presidential libraries had so much to offer.

What route do you recommend for someone who wants to road trip for the first time?

L: I think Route 50 was one of the nicest. If you can stay off the main highways, do it. The interstates are beautiful things for when you want to get somewhere fast, but you miss everything.

There’s so much to see. What should someone base their route on when planning?

L: No matter what you’re interested in look for things that are in that area. Like history, if you’re interested in battlefields you could spend months visiting them all in the southeast. Or if you find a writer you’re interested in...anything!

M: Just seeing the country and riding along.

L: We’ve got friends who like to go to zoos. They just travel all around the country going to zoos. It’s whatever you’re interested in.

M: I wanted to go to Savannah because I heard there was a museum here that had Scarlett O’Hara’s dress from Gone with the Wind. I was so excited because that’s one of my favorite movies. I never thought i’d be able to do that. Especially because I never traveled when I was younger, so it’s amazing to be able to hop in the motorhome, drive down and see something as ridiculous as Scarlett O’Hara’s gown.

L: One time we tried to hit as many national forests and parks as we could.

Has anything you’ve seen changed your perspective?

L: It’s changed our outlook on life. Before we started traveling the north east was basically it. Yea, I’d gone down south a few times for the service. But I’ve probably never gone more than 100 miles from the Atlantic Ocean. And it’s amazing. I thought everyone in the world lived in New York City; that was civilization. Then you find out Chicago is bigger. And the first time we went across country, to see how big this country is, where you’re driving and you can see fifty miles ahead, drive for hours and see nothing else. You can’t wrap your head around that or visualize that from reading a book or watching TV. You can’t appreciate it until you see it. And to see how different people live. It’s changing a bit now. But we’d hit totally different cultures and foods. I do carpenter work and I’ve seen carpenters make the same thing I make but in totally different ways, with different tools and different methods. That’s where you learn things.

So, you guys are the cool nomadic kids in your friend group.

M: Yea.

L: We dare a little more.

M: Some of our friends don’t follow us cause they feel we’re too old. They don’t want to get off the beaten path.

L: We’ll just go and if we stop, we’ll stop. We’re a little more daring, but everyone is different. It’s still nice to get home. Then regroup, reorganize and then take off again.

by Cassia Reynolds

Disclaimer: I know cartographartist isn’t a real word. But it should be.

I first discovered the work of Dave Imus, the founder of Imus Geographics and winner of four top national awards for cartography (as well as six other runner up places), while on a mission to find a map to represent the Flyoverlands logo.

Samantha and I had already spent a week searching for the right map to fit our vision. We wanted something detailed, readable, and representative of the actual landscape of the United States. Basically, we wanted the map to demonstrate what we hoped to do with our blog: explore America. We’d both noticed a trend in the maps we’d found so far; they were very colorful and overwhelmed with labels, but not particularly informative of the nature and distinctions in US geography.

The hunt led me to a Slate article about Dave’s most famous map, The Essential Geography of the United States of America, which won the Best of Show award by the Cartography and Geographic Information Society in 2012. From afar, it looked like a simple, 4ft x 3ft rendering of the United States. It was pleasing to the eye, a well-shaded illustration of geographic changes with clear lines marking state borders, rivers, mountains, and other important landmarks. However, the real genius of the map is in the attention to detail; I learned Dave illustrated and labeled his work over the course of two years. He included 1000 iconic American landmarks and did it all without sacrificing topographic detail for political information.

When I reached out to Dave about possibly using his illustration for the Flyoverlands logo, he not only agreed to it, but to an interview as well. And that’s how I got a little one-on-one time with the man who single-handedly beat out big companies like National Geographic and Rand McNally for this prestigious award in mapmaking. And I found out that not only does Dave not have formal training specifically in cartography, but that he really only started Imus Geographics back in 1983 because his lack of experience meant he couldn’t land a job as a cartographer.

Over the course of a half hour, we discussed Dave’s love of road trips, his beef with geography in the American education system, and the DL on what really goes into making one of his mapsterpieces (BAM I’m on a roll today).

Tell me about your work as a cartographer.

I have very little in common with my colleagues across the country. I live in a pretty artistic community, Eugene, Oregon, and I have way more in common with woodworkers and painters and sculptors than I do with mapmakers. I’m an illustrator, an artist. And mapmaking is primarily a technical activity. It’s data manipulation and interpretation and once this data is somehow represented, it’s done. It’s like, “We have the data published!” And [I say], “Oh yay, that’s a good place to start. Now let’s make a beautiful illustration that really says something.”

What goes into making a map? Does it require you to experience the places you’re mapping out?

If I’m mapping a city I’ve never been to, I want to capture the essence of that city. So I read about it and I study large scale maps of it to see which of the principal routes I want to put on my map and what, if any, iconic landmarks are there that sort of identify it as a place. And so I experience the place whether I’ve been there or not. I’ve got to contemplate it and try to make sense out of it so that somebody who’s looking at my map will know the basic geography of the place just like people who live there.

What’s been your most difficult project and your favorite project?

The way that my career path has gone is each project is more difficult and more fun. For many years I have worked with a colleague in Massachusetts. And we were talking about how complicated we make things. And he said, “You know, if it were easy, we wouldn’t be interested!” And I said, “You know, I think you’re right.” But the US map took everything I knew about map making and geography to do it.

What do you want people to know about your award winning map, The Essential Geography of the United States of America?

The big thing really about that map is that it’s made with an entirely different standard of artistry than American cartographers embrace. I control every detail of the map so it’s all my interpretation of how best to communicate the geography of one area. I’m not letting algorithms do a dang thing. I use a computer but I use it as a drafting tool. So the map has far greater clarity. It’s just easier on the eye and more acceptable to the mind. And the other thing is that it’s the only map of basic geography. It shows where the country is forested and where it’s not. It has the principle populated places so people know what the important locations of an area are. And it’s got stuff like “the Bluegrass Country of Kentucky” on it. Because we care about these places but we don’t know exactly where they are.

Do you see your work as an education tool for others?

In primary and secondary education, geography bores even me. It’s treated like some sort of abstraction. Look up a map by Rand McNally or National Geographic or United States Maps and they treat the world like it’s some sort of abstraction that doesn’t even really exist. [Their maps] might look like a moonscape. They’re just a whole bunch of bright colors but they’re not illustrations of the land. A good map is an illustration of the land first and it’s only a map because you put type tables on it. If you’re not illustrating the land with the artistic attention of a botanical illustrator or a medical illustrator, then you’re not illustrating the land in a way where people can actually make sense out of it. You don’t actually have to see a wild iris because people draw beautiful pictures of them. Nobody draws beautiful pictures of basic geography and puts these labels on them so we know what we’re looking at.

As someone that’s spent so much time going over America’s geography, what are three pieces of advice you have for the American road tripper?

I’m an expert road tripper by the way - I’m exploring all the time. This traveling partner [and I] go on trips for a couple thousand miles and we don’t drive an inch on the freeway. You see so much more of America that way. I mean this is planet earth we’re talking about here! Which as far as we know is the most exotic planet in the universe. So you know whether you’re out in the middle of Kansas or you’re in the canyon lands of southern Utah, it’s beautiful and interesting.

Tell me something you love about the USA.

We have so much to learn from each other. I think that some time in the future, and I hope it’s not too long, people will come from all over the world to visit our Native American reservations. They don’t have them anywhere else. You can still go to the Hopi reservation and, man, people are living there the way they’ve been living for 2000 years basically. They’re still doing the same ceremonies and stuff and it’s really cool.

Dave has now begun a quest to break down the boundaries further between cartography and fine art, transforming his geographic illustrations into high-quality canvas prints that highlight the beauty and intricacy of landscapes. His individual pieces focus on regions like the Great Lakes, or single states, like Iowa and Alaska. They expose the details of the cities, roads, forests, and mountains of these areas in a totally new light.

Or, as Dave put it, “Every state looks cool. Iowa looks cool!”

His current show, “ReEnvisioning Maps: The Cartographic Art of Dave Imus,” in the gallery space of InEugene Real Estate in Eugene, Oregon, began on November 6 and runs through December 2015. Check out the press release for more information, visit Dave’s website, and/or Like Dave's Facebook page, The Essential Geography of the United States of America.

by Cassia Reynolds

You’ve spent the last eight hours locked in a car. Everything has begun to bleed together into that endless interstate continuum. When the fuel indicator flashes an insistent red, a wave of relief passes through you. You pull under the neon awning of the next gas station and as you open the car door, you flop out onto the cement.

Your body is heavy with that special lazy kind of soreness. Your mind is completely fizzled, half-stoned with that long distance driving daze. And as you fuel up, a tender pinging flutters through your stomach, soft but tugging. Feed me, it whines.

When you enter the gas station you’re assaulted by an artillery of smells: preservatives, grease, freeze-dried eggs, and tile cleaner. But in your weakened state you can’t tell if your nose is tingling because it’s warning you of possible poison or if it’s lusting for the source of those sterile-but-greasy fumes.

Are you hallucinating or do those grayish sausages on that open grill smell really good?

And suddenly you’re standing in front of that bacteria-infested grill, a set of plastic tongs in one hand and a paper sausage holder in another. Your mind snaps awake and you drop the tongs, stepping back in horror.

The sausages taunt you, bulbous and speckled unnatural colors. Several are oozing a pus-like yellow liquid onto the grill. Fuck no. Then you take in another deep whiff of hot, meaty goodness. Your stomach is growling. But the fear is too much. Your mind is lost, your decision is unmade, and you leave with just a packet of chips in hand, your true hunger unquenched.

If this sounds familiar, don’t be ashamed; we’ve all had our moment in the gas station, weighing the pros and cons of a questionable food product. And it’s time for someone to take a stand against the uncertainty!

This food pioneer has embarked on a noble quest for the betterment of mankind: to venture into the unknown hazards and test the smelliest, the most mysterious, and the least appealing of all the pre-packaged and quasi-edible. Just for you. And for science, of course.

At first glance, the mini-cauldron filled with steaming peanut soup confused me. I’m Southern and I’ve eaten boiled peanuts plenty, but they’ve never been soaked in some strange, glowing orange broth. Seriously, this stuff radiated the kind of alluring glow that gold coins did in that old cartoon, Ducktales.

As if to counter the inedible-like ambiance, it also emitted a pleasant, spicy-salty scent that reminded me of gumbo. I attributed it to the cajun seasoning.

I picked out the smallest foam cup and dipped the soup ladle deep into the pot, stirring up the layers of orange-speckled, peanut lumps. Before I dumped a spoonful into my cup, I drained a bit of the hot liquid out. That just seemed damned unsafe for a car snack; I envisioned burnt thighs, stained seats, and a forever lingering smell of cajun seasoning.

Back in my car, I placed the cup in the drink holder beside me. I knew I couldn’t eat this snack and drive; it was way too messy. The first peanut I picked out of the bunch burned hot between my fingertips and I had to drop it and wait a moment before digging in. When I did, I wasn’t sure how to eat these things; I know you don’t normally consume the shell of a boiled peanut, but this one was particularly soft. I decided against it, peeling it open. I dug one meaty half out of a shell and popped it in my mouth.

It was hot, with a smooth, thick texture just a degree away from mushy. It fell apart without resistance between my teeth. As it did, the juices burst across my tongue. The flavor was intense and on the saltier side, but held heavy overtones of pepper and creamy nuttiness that came in waves as I chewed and swallowed. This was no snack to take lightly; it had an explosive, fiery zest.

I only made it through a few peanuts before I had to stop and take a break, fearing a sodium-overdose. The aftertaste held strong and didn’t fade until several sips of coffee later.

The peanuts came with a major downside: every bite meant wiping my fingers on napkins. I couldn’t possibly drive and eat these things at the same time. The smell also lingered forever, even after I closed the lid on the cup and wrapped it up in a trash bag.

Fast Forward Two Hours Later. My stomach is feeling fine, no problematic after effects, except for a slight salty taste in my mouth.

Conclusion: This is an offensive, awesome visual and olfactory experience. It’s also quite tasty, with a distinct cajun spiciness. However, if you’re the one in the driver seat, it’s just not a viable snack. You will get cajun peanut drip all over you and it will smell up the whole car. It’s also not very filling for the price.

by Samantha Adler

The rolling forests of the Northeast and Mid-Atlantic are entirely engulfing. With their blue and green hues, dewy crisp breath, lush foliage, and temperamental, seasonal mood swings.

A seemingly odd find in the heart of the American wilderness was a parking lot. An empty, expansive lot, dropped atop a mountain.

That asphalt slab was strangely patriotic. Even amidst the defining, impressive backcountry, I felt a surprising fondness towards the lot. It was a familiar and comfortable sanctuary after five hours of driving through, up, and over many mountains.

The US has always been a wild country of explorers and adventurers. Now, we’re leading modern expeditions in Jeeps and Priuses.

Repetitive lines on blacktop mark a place to rest, park your gas-powered stead, and admire the complexity of this huge country. Whether you’re cutting through the suburban jungle, city bustle, towering forests, or flat, flat desert.

Parking lots are the watering holes of America, a microcosm of its diversity, its good and its bad. To dogs waiting patiently with tongues wagging, notes of kindness left stuck on windshield wipers, helping hands carrying heavy loads for those in need, laughter from impromptu cookouts on pick-up beds. To unwanted stalkers, boisterous and vile exchanges, newly discovered dents and paint chips, and hidden dangers in the absence of street lamps.

These parking lots are definitively American to me. They’re relics of a country of explorers behind the wheel.

by Cassia Reynolds

I have a special place in my heart for the highways of the American Midwest, yellow dotted lines on straight, wide strips of black speckled asphalt. It’s a timeless love for the scenery: a big, empty sky over endless, flat, green farmscapes. Maybe aesthetically I’m a minimalist; there’s just something mesmerizingly simple about all that open space. I can stare out the window for hours, getting thrills from the sparse huddles of cylindrical granaries that rise above the cornfields or the single hilltop adorned with a quaint, red-painted barn, breaking up the monotony.

And maybe that’s it; the terrain is so boring that I begin to appreciate the beauty of the small things that I see.

Whatever it is, I’m drawn to the quiet charm of this place. To the trees: pines, oaks, firs, spruces, and maples. To the neighborhoods with brick houses and freshly-cut front lawns and barefoot kids running through the grass. To the busy parking lots of the shopping malls with their perfect, infinite rows of soccer mom minivans and SUVs and shiny paint jobs that glint under the sun. To the temperate climate, with its four distinct seasons that perfectly balance a brutally cold winter with a swampy-hot summer. To the parks and lakes and fields and green, green, green everywhere and everything.

It’s what I imagine as definitively American in a land that’s so large and compartmentalized and spread out that it feels like five countries in one sometimes.

It’s a quiet, flat place, with not a lot happening.