Black Hills, South Dakota

by Cassia Reynolds

Check out my first Mount Rushmore installment: Unnatural Habitats.

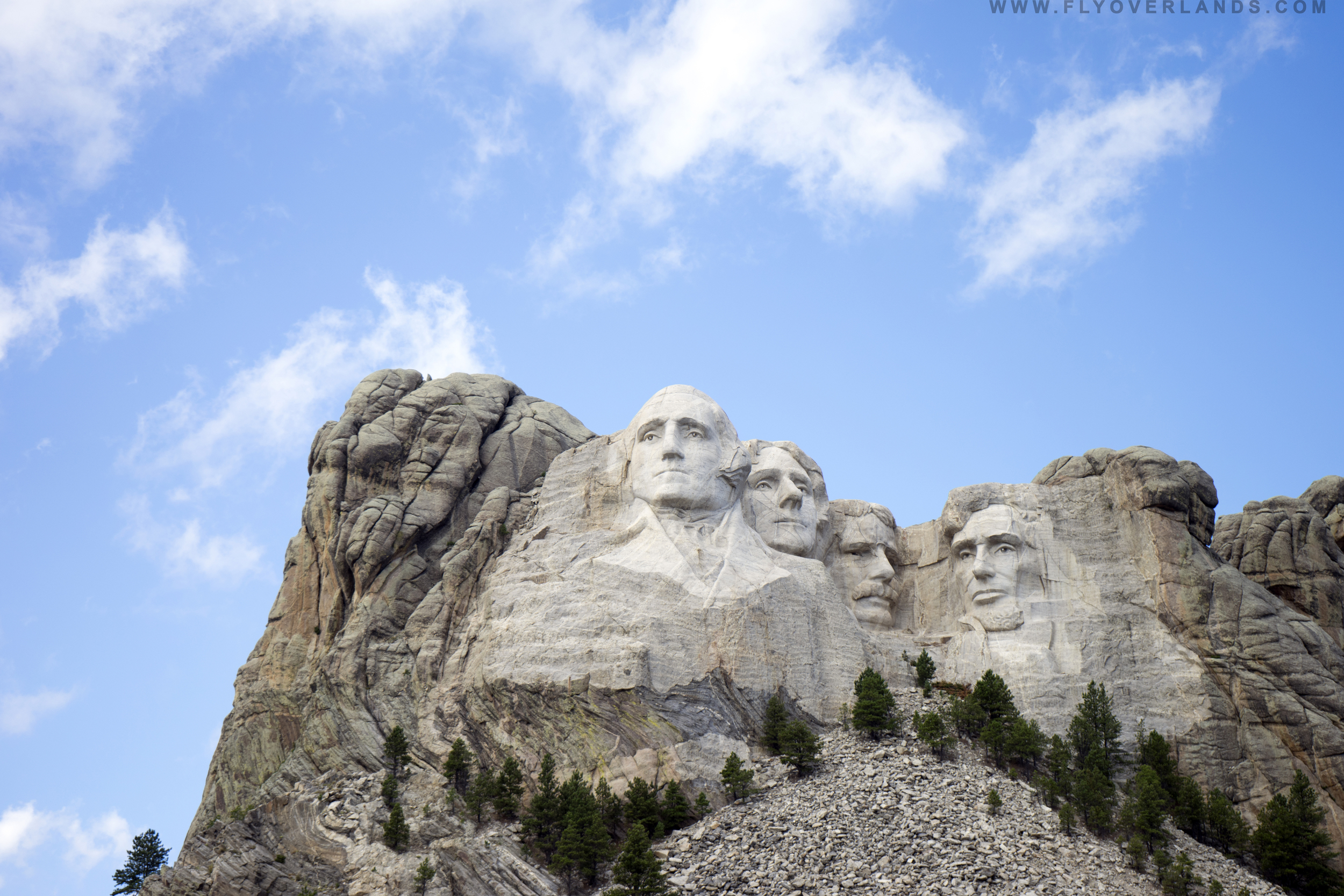

The sun’s rays shone bright on the pale, creamy stone faces set against the Crayola Cornflower Blue backdrop. Afternoon shadows accented an overhanging brow, a stern jawline, a pensive gaze. A soft, surreal daze settled over me as I stood on the viewing platform before Washington, Jefferson, Roosevelt, and Lincoln, ruminating on the postcard perfect scenery.

Do these sculptures feel so familiar because they’re accurate representations of the presidents whose faces I’ve memorized over the years? Or has Mount Rushmore so shaped my mental image of these presidents that looking at it in person just affirms my vision of these men?

It wasn’t until later that I learned the incredible efforts undergone to position Mount Rushmore to leave viewers like myself so spellbound: the visionary’s tireless quest for the landscape with perfect lighting and texture; the two full years of sculpting that went into the original bust of Jefferson, just to be dynamited and repositioned on Washington’s right; and the thousands of measurements that were calculated and then multiplied by twelve to recreate the original model of the four figures. (Check it out.)

But in the present moment a vivid but brief movie clip materialized in my memory. It was a scene from the 1994 Macaulay Culkin classic, Ri¢hie Ri¢h. Ri¢hie and his mother were perched on the edge of one stone eye socket in Mount Ri¢hmore, clinging desperately to each other. Ri¢hie’s dad dangled perilously (and ironically) from the carved glasses on the nose of his own likeness.

I squinted hard at Mount Rushmore, wondering if my childhood truths could possibly have grounding in reality. But if there were any doorways set in the pupils of the monoliths, they were invisible from this distance. The sixty foot replicas of America’s great leaders stared blankly ahead, unwilling to give even the barest of hints.

So instead I Googled. And not only did I find out that in 1998 the National Parks System constructed a Hall of Records within the memorial that contains sixteen porcelain enamel panels detailing the Constitution, the Declaration of Independence, and other historic records, but also the background of one of America’s most iconic national memorials.

As with most wildly passionate, ambitious projects, a crazy man was at the center of all the fuss. In this case, a crazy Dutch-American man named John Gutzon de la Mothe Borglum: an Idaho-born, eccentric perfectionist, Ku Klux Klan sympathist, nativist, painter, and (of course) sculptor.

Borglum was, while extremely qualified to construct larger-than-life replicas of famous national figures, also known for being hot tempered, egotistical, and more than a little batshit. He’d actually quit the last project he’d been commissioned to work on in Georgia (a memorial to the heroes of the Confederacy with a side altar dedicated to the KKK) in a rage after a dispute with the association, smashing all his clay and plaster models during his dramatic exit.

Side note: As unfortunate and disrespectful as it is, given Borglum’s history, it makes sense why he chose the American presidents for his work instead of the Native American leaders whose sacred land he worked on.

Borglum was born in 1867 to one of the wives of a Mormon bigamist. His father worked as a woodcarver before attending Saint Louis Homeopathic Medical College and opening his own practice in Nebraska. When he was sixteen, Borglum studied art in Los Angeles, specializing in painting, and married a divorcee eighteen years his senior. After a few more years training in Paris, Borglum made a sudden switch to sculpting (rumors go that it was just to compete with his younger brother, Solon, who was already an established sculptor). For more information on Borglum, check out his biography on PBS.

In a selection from a Smithsonian article on the history of Mount Rushmore, his son, Lincoln Borglum, describes his father’s perspective on art.

Borglum was of the mindset that American art should be “…built into, cut into, the crust of this earth so that those records would have to melt or by wind be worn to dust before the record…could, as Lincoln said, ‘perish from the earth.’” When he carved his presidential portraits into the stable granite of Mount Rushmore, he fully intended for the memorial to endure, like Stonehenge, long past people’s understanding of it.